REGARDS TO

THE END

“Surprise and precision are Wells’ greatest assets as a composer, and Regards to the End is filled with both.”

— PITCHFORK

“Like the artists and activists she memorializes, Wells herself creates art that speaks to the masses and extends heart-felt pleas for better.”

— VINYL ME PLEASE

“Smolders and scorches.”

— WNYC NEW SOUNDS

“Wells’ skill as an arranger, producer and master of a small orchestra’s worth of instruments gives Regards to the End a gorgeous sense of theatricality.”

— THE LINE OF BEST FIT

“I’M JUST A FIRE,”

Emily Wells sings on her album Regards to the End, her ethereal warble floating over a backbeat of drums. “Burn everything in sight.” And so she does, in a new body of work that smolders and scorches, wounding and illuminating in equal turn. The polymathic composer, producer, and video artist explores the AIDS crisis, climate change, and her lived experience—as a queer musician from a long line of preachers, watching the world burn—in immaculately layered yet spare songs that impel the listener to be attuned, acting like a magnet on our attention.

Wells, a multi-instrumentalist who comes from a classical background in violin, often thinks in terms of an ensemble while composing. Along with a roster of contributors including her father, a French horn player and former music minister, she builds the songs on Regards to the End from deliberate strata of vocals, synths, drums, piano, string instruments (violin, cello, bass), and wind instruments (clarinet, flute, French horn). The music is numinous in part because the listening experience is a resoundingly bodied one. The vocals and winds, a strong presence on the album, foreground breath. Life—unsanitary, beautiful, persistent, brief—swells inside of every note. Drums tie us to the pulse of our heartbeats, rooting and grounding us.

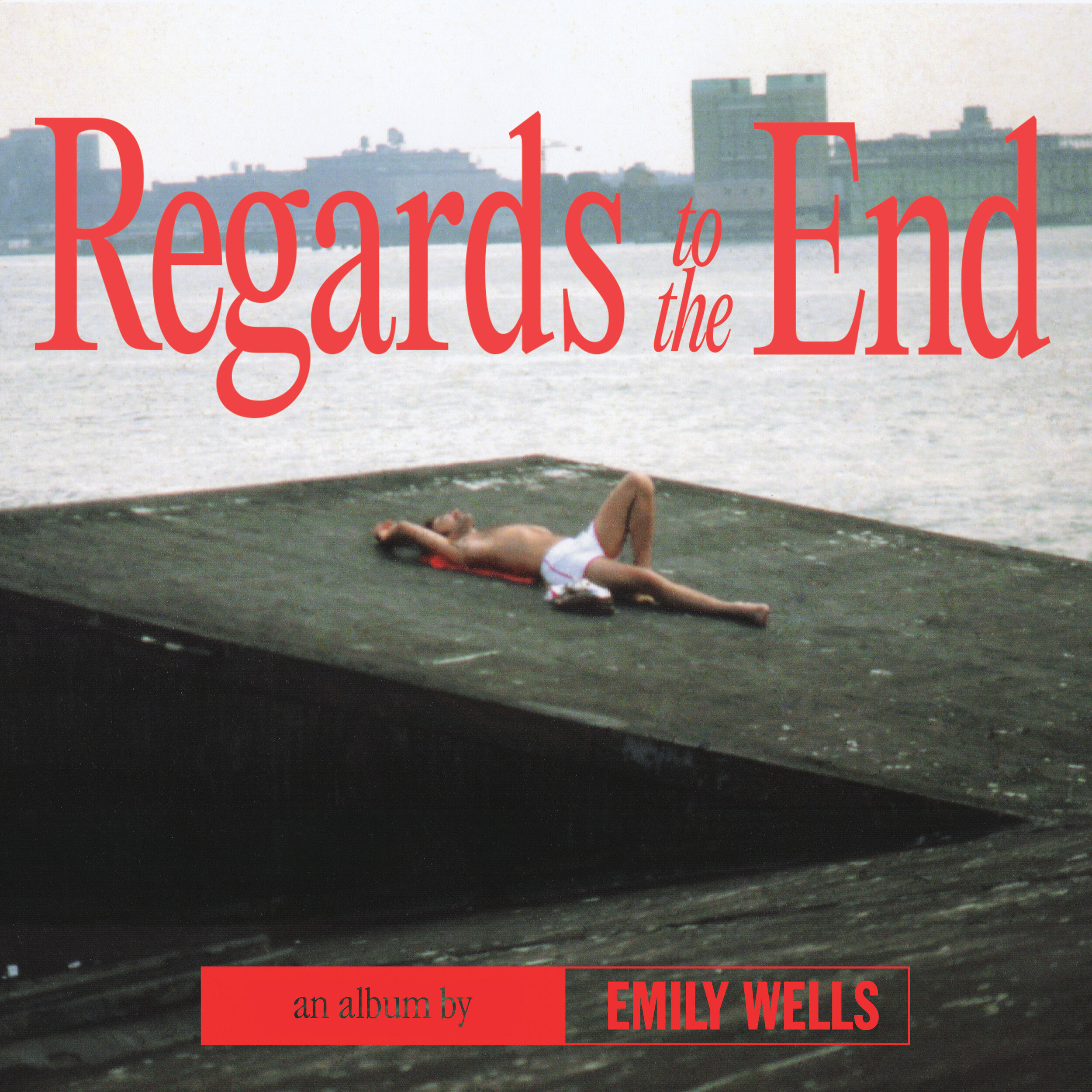

Album design Julia Fletcher, featuring The Piers (exterior with person sunbathing), courtesy of the Alvin Baltrop Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The body is cardinal, here, running through the ten-song album like a red thread. The body is an animal, a number, a puppet. The body wishes it were dancing. The body is tethered and doesn’t know if it wants to be. Where would it run if it weren’t? Wells’s poetic lyrics never say it explicitly, but a body is not an easy thing to inhabit in a time of viral pandemics, changing climates, and a host of other humanitarian and planetary disasters. “Some kind of violence you feel in the body, my body, my body,” Wells cantillates in “Blood Brother.” “Do it in remembrance of me,” she adds, bringing an intimate valence to a biblical sentiment. It’s worth remembering that the millennia-old practice of taking Communion—symbolically consuming the body and blood of Christ to commemorate his death—is fundamentally an act of embodied empathy that acknowledges earthly suffering; taking place in the dark of our innermost chambers, the experience of such radical proximity may be visceral, even erotic.

Wells’s music is its own kind of spiritual communion, shot through with fierce empathy and justified rage. Speaking about her 2019 album This World is Too _____ For You in an interview with Flaunt, Wells said: “Each day I encountered a form of friendship with all those who had been artists before me, all reaching out to touch this thing we don’t name unless we call it god. You heard the cry and you want to cry back.” This deeply felt connection with artists across time is also knit into the fabric of Regards to the End. The album is informed by the lives and work of choreographers and visual artists, particularly those with ties to the AIDS crisis.

Wells’s constellation of reference points includes Félix González-Torres (1957-1996), who made tender installations devoted to his lover, who died from AIDS-related complications; Jenny Holzer (b. 1950), a conceptual and frequently text-based artist who contributed to the New York City AIDS Memorial; and Kiki Smith (b. 1954), who has centered the human body and its fluids in her sculptures and lost a sister to AIDS. For the album cover, Wells selected an image by Bronx-born photographer Alvin Baltrop (1948-2004), who documented the beauty of Manhattan’s decrepit West Side piers, a gay cruising ground, in the 1970s and ‘80s. Titled “The Piers (exterior with person sunbathing)” (1980), the quiet photo depicts a solitary supine man on a stretch of pier. He looks like he might be dreaming.

One lodestar for Wells is David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992), an East Village artist, writer, and passionate AIDS activist who was also briefly in an experimental post-punk band called 3 Teens Kill 4. Wojnarowicz, whose searing work frequently referenced the government’s murderous inaction surrounding the AIDS epidemic, hung around the same piers that Baltrop photographed. As he wandered the excoriated cruising site, Wojnarowicz tossed seeds in hopes that grass would grow. “Throw a little grass out, then go lie among the weeds,” Wells intones in “David’s Got a Problem,” an atmospheric and gentle number with a stripped-down quality that lucidly evokes the simple, quietly hopeful act of scattering seeds in the face of neglect or even condemnation. In many ways, the AIDS crisis and the climate crisis are profoundly different. Something they share, however, is the treatment of what we know to be indispensable—humanity, the environment—as disposable.

Wells reflects on the daily experience of walking in the woods during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in a reverberant track with live drums. Titled “The Dress Rehearsal,” after the notion that the pandemic is a “dress rehearsal” for the horrors of climate change, the song gestures at nature as a place where love is deeply embedded. “Where nothing is still, love happened here,” Wells sings powerfully, her expansive voice creating space for mourning and celebration, rage and hope, and perhaps above all, acknowledgement. The words “love happened here” also appear in a public art project by Nayland Blake, which utilized vinyl stickers—widely disseminated, like seeds—to encourage AIDS awareness in the 21st century, at a time when many have gone silent on the issue. Silence, as we’ve learned, equals death. Silence, apathy, ignorance, denial: these are luxuries that Wells knows we cannot afford, as we make our way from the fraught present into an even more unforgiving future.

One gut-wrenching track centers around Bill T. Jones (b. 1952) and Arnie Zane (1948-1988), partners in art and love who cofounded a legendary avant-garde dance company in 1983. Wells lingers on the night of March 30, 1988, when Zane died from AIDS-related lymphoma and, due to the stigmas and fears surrounding the disease, the medics wouldn’t touch him. In his 1995 memoir Last Night on Earth, Jones wrote: “When I am in pain, I must know that beauty has always been and always will be. This is as close to eternity as I need to be.” “Arnie and Bill, Arnie and Bill, to the rescue,” Wells sings repeatedly, slowly, deliberately. It’s a refrain, a requiem, a gift.

–Cassie Packard

With support from: The NYC Women’s Fund for Media, Music and Theatre by the City of New York Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment in association with The New York Foundation for the Arts.

© ℗ Emily Wells 2022 • Thesis & Instinct Records & This Is Meru • Exclusively distributed by Secretly Distribution